Why Raila Odinga Is an Enigma in Kenyan Politics

- Darn

- Oct 16, 2025

- 13 min read

Few figures in Kenya’s political history have inspired as much admiration, controversy, and curiosity as Raila Odinga. Loved, feared, and endlessly analyzed, he remains the puzzle that every election tries, and fails, to solve.

Table of Contents

Born into power but schooled in rebellion

Opposition firebrand and constitutional reformer

Perennial presidential candidate

Handshakes as crisis management and self‑preservation

How handshakes fed the enigma narrative

Contributions to democracy and reform

Controversies and allegations of opportunism

Electoral politics and ethnicity

Protests, MoU and the twilight of his influence

Death and tributes

It is rare for a politician to inspire devotion and suspicion in equal measure. Raila Amolo Odinga, the scion of a political dynasty turned opposition icon, did just that, earning the title “Enigma of Kenyan politics” not merely from a 2006 biography but from a career that spanned coups, detentions, mass movements, power‑sharing deals and near‑misses at the presidency [1]. Even in death, the questions he provokes about Kenya’s political soul like why his reformist zeal coexisted with opportunistic alliances and why his handshakes could either calm a nation or inflame it continue to animate debate.

The making of the enigma

Born into power but schooled in rebellion

Raila Odinga was born in 1945 into one of Kenya’s most prominent families. His father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, served as Kenya’s first vice‑president but resigned after falling out with President Jomo Kenyatta, creating a legacy of dissent that his son would inherit [2]. Trained as a mechanical engineer in East Germany, Raila returned home during Daniel arap Moi’s autocratic rule [3]. He first entered elective politics after enduring nearly a decade in detention for alleged involvement in the 1982 coup attempt against Moi [4]. His imprisonment, nine years in total, with six years spent in solitary confinement [5], turned him into a symbol of resistance and honed his ability to use adversity to build political capital. Supporters would later call him Baba (father) for his paternalistic care, while his Luo nickname Agwambo, meaning “mysterious one”, reflected a perception that he manoeuvred with almost supernatural cunning [6].

Opposition firebrand and constitutional reformer

Odinga’s early activism fused ideological radicalism with practical politics. After his detention, he won a parliamentary seat in 1992 and quickly became an outspoken advocate for multiparty democracy and constitutional reform. He was instrumental in protests that pressured the Moi regime to legalise multiparty politics in 1991 [7] and, later, played a significant role in the passage of Kenya’s transformative 2010 constitution [7]. His supporters credit him with embedding civil liberties in law, yet his critics note that he often circumvented democratic norms when convenient. Still, the tension between principle and pragmatism explains why he could spearhead a constitutional referendum against his ally‑turned‑foe President Mwai Kibaki in 2005 and thereafter convert the ‘No’ campaign into the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) [8].

Perennial presidential candidate

Odinga’s five runs for the presidency anchored his enigmatic reputation. In 1997 he ran under the National Development Party (NDP) and finished a strong third behind Moi and the Democratic Party’s Mwai Kibaki [9]. Following the 1997 loss, he dissolved NDP and negotiated a surprise merger with Moi’s ruling KANU in 2001 that earned him the Energy minister’s portfolio [10]. To critics this was cynical opportunism; to his allies it was strategic engagement [11]. When Moi anointed Uhuru Kenyatta as successor, Odinga defected and orchestrated the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), famously declaring “Kibaki Tosha” (Kibaki is the one) to rally the opposition [12]. The coalition defeated KANU in 2002, and Odinga became Roads Minister [13] before falling out with Kibaki over constitutional reform [8].

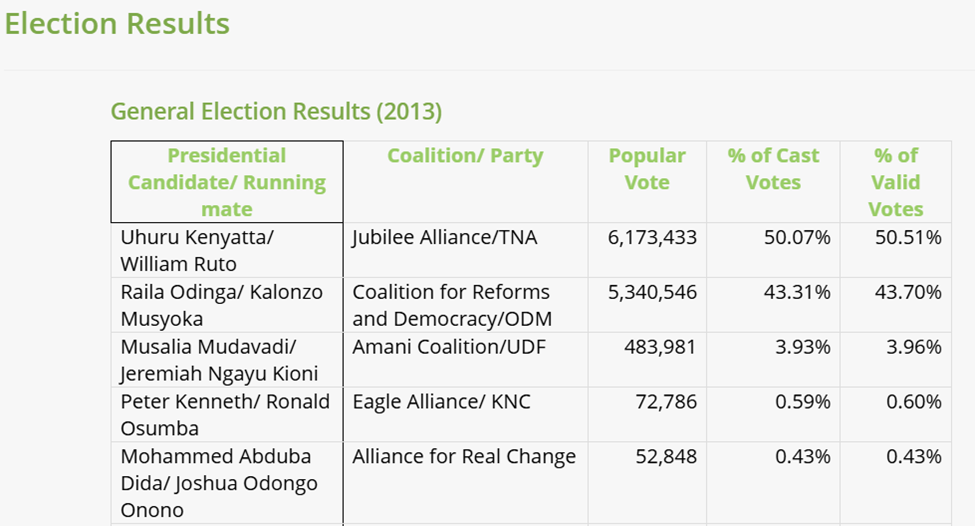

His 2007 presidential bid under ODM ended in disaster: the Electoral Commission declared Kibaki winner amid widespread allegations of rigging, triggering violence that left more than 1,000 people dead and displaced hundreds of thousands [14]. International mediation led to the creation of a grand coalition; Odinga accepted the newly created post of prime minister [15]. The compromise quelled violence but left many questioning whether he had legitimised a fraudulent vote. In 2013 he ran again, this time under the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD). He lost to Uhuru Kenyatta but captured a formidable 43.7 % of the vote [16], a testament to his enduring popularity. The Supreme Court dismissed his petition, and his acceptance of the verdict showed statesmanship but frustrated supporters who believed he had been robbed again.

The 2017 election epitomised the Odinga paradox. Running as the National Super Alliance (NASA) candidate, he succeeded in having the Supreme Court annul the initial results, an unprecedented victory for electoral jurisprudence in Africa [17]. Yet he then boycotted the repeat poll, arguing that reforms had not been implemented, and theatrically swore himself in as the “People’s President” [18]. In 2022 he made his fifth bid, backed by incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta in the Azimio la Umoja-One Kenya coalition [19]. He lost narrowly to William Ruto; the Supreme Court again upheld the outcome [20]. The pattern, hard‑fought campaigns ending in alleged rigging, court battles, protests and eventual grudging acceptance or tactical retreat, reinforced his reputation as a perennial candidate and emboldened his narrative of stolen victories.

Master of handshake politics

Handshakes as crisis management and self‑preservation

No aspect of Odinga’s career exemplifies his enigmatic character more than his embrace of handshake politics, power‑sharing deals negotiated with rivals to resolve crises or secure influence. The term gained global attention after the surprise détente between Odinga and President Uhuru Kenyatta on 9 March 2018, known simply as “the Handshake.” Yet Odinga’s practice of negotiating truces dates back two decades.

The Star newspaper calls him the “Handshake King” and notes that he has executed four major pacts [21]. The first occurred after the 1997 election when he merged his NDP with Moi’s KANU and was rewarded with the Energy Ministry [10]. This alliance collapsed when Moi chose Kenyatta to succeed him, prompting Odinga’s “Kibaki Tosha” coalition [12]. The second handshake unfolded after the disputed 2007 vote, when the Kofi Annan–brokered agreement installed Odinga as prime minister in a grand coalition government [15]. The deal, though stabilising, entrenched ethnic divisions and produced a nusu mkate (“half‑loaf”) government that critics derided as an elite truce [22].

The third handshake came in March 2018. After the Supreme Court annulled the 2017 election and Odinga boycotted the re‑run, he surprised the nation by appearing at Harambee House with President Kenyatta to announce a truce and the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI). The BBI sought to restructure government and promote unity but was later struck down by courts [23]. Many of Odinga’s supporters viewed the handshake as betrayal because security forces had killed more than 70 protesters in the contested election’s aftermath [24]. Nonetheless, the deal secured Kenyatta’s backing for Odinga’s 2022 candidacy [25] and gave Odinga significant influence within government.

A fourth handshake emerged in March 2025, when Odinga signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with President William Ruto [26]. The Daily Nation reported that pre‑signing hype portrayed the MoU as an imminent power‑sharing arrangement that might even delay Odinga’s 2027 ambitions, but the document turned out to be a loose cooperation focusing on implementing the National Dialogue Committee report and broad governance reforms [27]. Ruto and Odinga emphasised that it was not a coalition [28], yet the pact effectively ended mass protests and allowed Odinga allies to join government. As Al Jazeera observed, handshake politics in Kenya is often “elite self‑preservation disguised as compromise,” and Odinga has executed a deal with every president since 2000 [29]. These handshakes have, at different times, prevented Kenya from sliding into violence and conferred Odinga seats at the table, but they have also drawn accusations that he traded popular mandates for personal or ethnic gain.

How handshakes fed the enigma narrative

Odinga’s willingness to reconcile with adversaries strengthened his image as a pragmatic deal‑maker and a peacemaker. After the violence of 2007, the grand coalition government not only stabilised the country but also delivered key reforms such as the 2010 constitution [7]. His 2018 handshake with Kenyatta diffused tensions and allowed for a period of political calm and infrastructural cooperation (the BBI), although the courts eventually invalidated the initiative. His 2025 pact with Ruto ended months of anti‑government protests over the high cost of living and election grievances. In this sense, Odinga’s handshakes embody what Kenyans call “kuleta amani” — bringing peace.

Yet the same deals fed suspicions that he consistently bargained away reformist causes. Activist Patrick Gathara notes that Odinga has leveraged his popularity to access the spoils of power [30]. The 2000 merger with KANU outraged pro‑democracy advocates who felt betrayed by their hero [31]. The 2018 handshake, struck while police repression was fresh, damaged his credibility among young protesters and earned him the label of a co‑opted elder[32]. The 2025 MoU, coming on the heels of his failed bid for the African Union Commission (AUC) chairmanship, was interpreted by some as an attempt to secure a soft landing and ensure allies’ appointments [33]. Thus, while Odinga’s deals demonstrate political maturity, they also illustrate the contradictions at the heart of his enigma.

Major handshake deals and presidential bids

Year/Period | Context | Outcome |

1997–2001 | After finishing third in 1997 election, Odinga dissolved his National Development Party and merged with President Moi’s ruling KANU, becoming Energy Minister. | Secured cabinet post; alliance collapsed when Moi endorsed Kenyatta. |

2002 | Formed National Rainbow Coalition and endorsed Mwai Kibaki (“Kibaki Tosha”); served as Roads Minister. | Coalition ousted KANU; later split over constitutional reform. |

2008 | Disputed election sparked violence; handshake with Kibaki created a grand coalition, with Odinga as prime minister. | Stabilised country; facilitated 2010 constitution but entrenched elite power. |

2018 | After Supreme Court annulled 2017 election, Odinga boycotted re‑run but later shook hands with President Kenyatta, launching the Building Bridges Initiative. | Reduced tensions; BBI later struck down; prepared ground for Odinga’s 2022 bid. |

March 2025 | Following cost‑of‑living protests and his defeat in the AUC race, Odinga signed an MoU with President Ruto. | Suspended protests; allowed ODM allies into government; emphasised cooperation on reforms. |

Reformist, opportunist or both?

Contributions to democracy and reform

Odinga’s supporters regard him as Kenya’s foremost democracy warrior. His activism in the early 1990s contributed to the re‑establishment of multiparty democracy [7]. As a leader of the Orange movement, he campaigned against Kibaki’s proposed 2005 constitution and then fought for the progressive 2010 constitution, which expanded civil liberties and devolved power [8]. In parliament and cabinet, he championed infrastructure development; his tenure as Roads Minister saw major projects such as the expansion of Nairobi’s thoroughfares. As prime minister from 2008 to 2013, he co‑led a coalition that oversaw economic recovery after the post‑election crisis and shepherded constitutional reforms [22][36]. Even his decision to challenge the 2017 election in court strengthened Kenya’s jurisprudence and set a precedent for judicial independence [17].

Odinga’s continental vision further burnished his reformist credentials. Appointed as the African Union’s High Representative for Infrastructure Development in 2018, he promoted connectivity projects and pan‑African trade. African Union Commission chair Moussa Faki Mahamat praised him for his commitment to pan‑Africanism and infrastructure integration, noting that he brought “rich political experience” and a passion for continental integration [37]. In 2024, Odinga campaigned for the African Union Commission chairmanship, outlining a platform that emphasised economic transformation, gender equality, food security, climate action and peacebuilding [38]. Although he led the first two rounds of voting, he ultimately lost to Djibouti’s Mahmoud Ali Youssouf [39]. Youssouf later hailed Odinga as an inspirational figure who championed democracy and people‑centred development [40].

Controversies and allegations of opportunism

For every reform he championed, Odinga faced accusations of hypocrisy or self‑interest. Critics point to his readiness to align with former authoritarian figures such as Moi and his repeated mergers with ruling parties as evidence of opportunism [41]. The 2007 grand coalition government, while necessary to stop violence, was marred by corruption scandals, including a maize subsidy scheme that lined the pockets of politicians while citizens starved [42]. Even as he railed against graft, some of his allies were implicated in state scams, undermining his moral authority [43]. In 2023 the African Union terminated his role as High Representative for Infrastructure due to organisational restructuring [44]; the timing coincided with his call for nationwide protests against President Ruto, fuelling claims that his continental job had become a political bargaining chip.

His handshake with President Kenyatta in 2018 and later with Ruto in 2025 were widely criticised by younger activists and the new “Gen Z” movement, who saw these deals as the epitome of elite self‑preservation [45]. When Odinga signed the 2025 MoU after losing the AUC race, some supporters interpreted it as capitulation for personal gain or a bid to secure future appointments [33]. The recurring theme, protesting fiercely before entering negotiations, created the perception that he leveraged street power as a bargaining chip rather than as a principled tool for systemic change. This duality, where activism and accommodation intertwine, is central to understanding his enigmatic reputation.

Electoral politics and ethnicity

Odinga’s political base among the Luo and other marginalised communities remained steadfast. Even after repeated defeats, crowds in his strongholds like Kibera and Kisumu greeted him with reverence; Reuters noted that supporters called him “Baba” and refused to abandon him even when he was accused of exploiting ethnic divisions or striking self‑serving deals [6]. He argued that his presidential bids were about ending ethnic hegemony; in 2007 he famously declared that communities feel unsafe unless “their man is at the top” [46]. Yet his critics contend that he sometimes mobilised ethnic grievances for political gain, which contributed to the violence of 2007 and tensions in subsequent elections [47].

Ethnicity also influenced perceptions of his handshakes. Supporters from the Luo community saw the deals as pragmatic ways to ensure representation, while detractors from other regions viewed them as ploys to access patronage networks. In 2024 the impeachment of Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, a key figure from the Mt Kenya region, intensified talk that the 2025 Ruto-Odinga pact would reconfigure regional power, fuelling suspicion among Mt Kenya elites [48]. The interplay of ethnic calculus and national unity in Odinga’s politics underscores why he was simultaneously revered and mistrusted.

Pan‑African ambitions and continental legacy

Beyond Kenya, Odinga cultivated a pan‑African identity. At the launch of his African Union Commission candidacy, he declared that the continent needed an AU capable of “delivering on the priorities of the African peoples” and commanding global influence [49]. He promised to champion industrialisation, support the Africa Continental Free Trade Area, promote gender equality, and foster peace and security [50]. Though he lost the election, his candidacy was notable because it was endorsed by President Ruto, his former rival, demonstrating his ability to forge alliances beyond domestic politics. Youssouf, the eventual winner, praised Odinga for inspiring a generation of African leaders [40].

As the African Union’s High Representative for Infrastructure, Odinga worked to develop continental infrastructure and integration. Faki Mahamat, then AU Commission chair, praised his dedication to Pan‑Africanism and infrastructure development [37]. His advocacy contributed to raising the profile of projects like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), though the tangible impact of his tenure remains debated. His defeat in 2025 indicated both the limits of his continental influence and the shifting alliances within Africa’s diplomatic arena.

Final acts and the end of an era

Protests, MoU and the twilight of his influence

After the 2022 election, Odinga refused to recognise Ruto’s presidency, leading nationwide protests against the high cost of living and alleged electoral fraud [51]. These demonstrations, initially dominated by his supporters, were soon overtaken by a youth‑led “Gen Z” movement that demanded systemic change beyond traditional opposition politics [52]. Recognising that his influence was waning, Odinga signaled openness to dialogue. President Ruto, facing economic challenges and anticipating the 2027 election, also saw value in co‑opting Odinga’s base. Their March 2025 MoU temporarily ended street protests, emphasised inclusivity, youth empowerment, debt audits and anti‑corruption measures [53]. While the pact lacked concrete power‑sharing provisions, it hinted at possible constitutional amendments to create the post of prime minister — a position Odinga had previously held [54].

Death and tributes

On 15 October 2025, Odinga died of a heart attack while receiving medical treatment in Kerala, India [55]. Reuters reported that he had been receiving treatment when he suffered cardiac arrest, and his death prompted a seven‑day national mourning period [56]. Supporters gathered in his strongholds, chanting and mourning the man they affectionately called Baba [57]. Kenyan President William Ruto described Odinga as a champion of reforms whose conviction inspired generations [58], while former President Uhuru Kenyatta hailed him as “a father to the nation” whose legacy was etched in Kenya’s fabric [59]. Across Africa, leaders including Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan, Zambia’s Hakainde Hichilema and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa paid tribute, emphasizing his pan‑African contributions [60]. Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, who defeated him for the AUC chair, called him a “towering figure” whose commitment to democracy and development left an indelible mark [40].

So why is he an enigma?

Odinga’s enduring mystique arises from the tensions between his roles as reformer, populist, deal‑maker and opportunist. He championed multiparty democracy, constitutional reforms and pan‑African integration, yet he repeatedly entered into alliances with those he accused of undermining democracy. He mobilised crowds with fiery rhetoric only to negotiate behind closed doors. He insisted that elections were stolen yet accepted appointments in governments he claimed were illegitimate. He repeatedly reinvented himself, prisoner, opposition leader, prime minister, pan‑Africanist, in ways that confounded both supporters and foes.

Part of the enigma lies in Kenya’s political structure, which incentivises ethnic arithmetic and elite bargains. Handshakes have been used to avert violence and distribute spoils; as one commentator notes, “every politician has a chance to eat. Every deal is possible. No betrayal is unthinkable” [61]. Odinga mastered this system, using his popularity to extract concessions while insisting he fought for ordinary citizens. His ability to survive decades of electoral defeats and remain relevant attests to his political skill and to the deep grievances that his rhetoric tapped. Even his pan‑African ambitions reflected the duality, a genuine vision for continental unity and a personal quest for legacy.

Ultimately, Raila Odinga’s enigma stems from the contradiction between his role as a champion of democracy and his participation in elite bargains. His supporters celebrate his sacrifices, years in detention, near‑misses at the presidency, and relentless activism, as proof of integrity. His detractors see him as a chameleon who perpetually sought power through backroom deals. The truth likely lies between these extremes. Odinga’s life mirrors Kenya’s own struggles: a quest for freedom hampered by ethnic politics, reforms coupled with patronage, and hope tempered by compromise. In that sense, understanding Raila Odinga means grappling with the complexities of Kenyan politics itself. His death closes a chapter, but the debates he ignited about democracy, justice and political morality will endure.

Sources

[1] [24] [32] [43] Raila Odinga: The symbol and symptom of Kenya’s political tragedy | Opinions | Al Jazeera

[2] [3] [8] [9] [11] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [36] [39] [44] [51] Detention, constitutional reform and handshakes: Raila Odinga bows out at 80 - Capital Business

[4] [7] [14] [55] [59] [60] Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga dies of heart attack in India at 80 | Politics News | Al Jazeera

[5] [6] [46] [47] [56] [57] [58] Kenya's veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga dies at 80 | Reuters

[29] [30] [31] [41] [42] [45] [52] [61] Kenya’s handshake politics: Elite self-preservation disguised as compromise | Politics | Al Jazeera

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button.

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button.

R.I.P Rao

A very articulate master piece

A very articulate Tribute to Baba, Rip in Peace 🕊️

Rest in peace

forever in our souls